Phoebe the Revelator

Let's take an apocalyptic road trip with Phoebe Bridgers, stopping along the way to visit Blind Willie Johnson, the magical land of Oz, and some helpful climate writers.

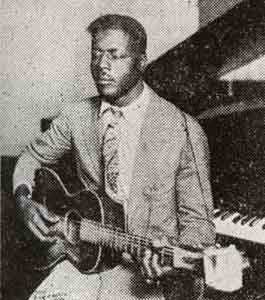

In 1930, a 33-year-old blues singer and evangelist known as Blind Willie Johnson travelled to Atlanta, Georgia to make the first recording of a song, possibly quite an old one, that's been performed, recorded and rewritten by many others since then.

The song, 'John the Revelator', is about John of Patmos, the author of the Bible's apocalyptic conclusion, the Book of Revelation. In Ancient Greek, ‘apocalypse’ means ‘uncovering’ or ‘revelation’. Traditional religious apocalyptic literature like the Book of Revelation depicts angels or other messengers sent by God to unveil truth. In Revelation, that truth is of end times. On "the great day of his wrath", as foretold by John, the earth quakes, the sun becomes black, the mountains fall, the forests burn, and the damned are tormented or slain.

In Revelation, Christ speaks through an angel who uncovers the truth for John of Patmos and for the reader. That angel tells John to "Write the things which thou hast seen, and the things which are, and the things which shall be hereafter." In doing so, John becomes his own kind of messenger.

In Blind Willie Johnson's telling, John's role really comes into focus. After all, by putting ink to parchment, it's he who becomes the 'Revelator'. "Well, who's that writin'?", Johnson calls out in his growling, gravelly voice three times in the song's first verse. He's answered by a woman who sings, "John the Revelator". In the next verse, the question becomes "What's John writin'?" The answer: "Ask the Revelator."

We can hear the two singers make the link between the act of writing and the act of revelation. By recording his visions and making the effort to transcribe them, John of Patmos becomes a divine messenger himself, or as the song's great rhyme has it, "John the Revelator, great advocator". The singer-preacher sees John uncovering the truth in the act of writing and suggests that if we "ask the Revelator", by cracking open a Bible, we can access that truth for ourselves.

In contemporary apocalyptic literature, with God long rumoured to be dead, there's no divine messenger. The author conjures up their own visions, extrapolating upon what's happening around them to create a depiction, perhaps even a prophecy, which is its own uncovering of truth.

The apocalyptic has proven fertile ground for novels, TV, paintings, video games and popular music. Over decades, the end of days has played out over and over again on the radio: Bob Dylan warned that 'A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall', Prince said he'd party like it was '1999', even as the bombs fell ("You can't run from the revelation"), and Britney said she'd keep dancing 'Till the World Ends'.

One of my favourite anthems of apocalypse is Phoebe Bridgers' 'I Know the End', the final song on her excellent 2020 album, Punisher. It's an apocalyptic vision, frightening and cathartic, that reveals a dystopia of malaise and boredom.

There's a sense of emptiness and restlessness that accompany the singer throughout. The song begins in transit:

Somewhere in Germany, but I can't place it

Man, I hate this part of Texas

Close my eyes, fantasize

Three clicks and I'm home

When I get back I'll lay around

Then I'll get up and lay back down

Romanticize a quiet life

There's no place like my room

The singer, tired of touring and travelling, fantasises about having her own pair of ruby slippers, able to transport her back to where she came from. For her, unlike Dorothy, it's not the home, with its associations of family life, that there's 'no place like', but the bedroom: private, even isolated.

That isolation is underlined in the first two lines of the first chorus:

But you had to go, I know, I know, I know

Like a wave that crashed and melted on the shore

We're told the longed-for home won't be the same; someone significant has gone. We also get our first sense of a natural end, an unavoidable disintegration, though, at this stage, the melting wave represents a loss that is personal.

But the following lines give a sense that the crisis may be broader:

Not even the burnouts are out here anymore

And you had to go, I know, I know, I know

Bridgers explained in an interview with Genius, "The kids that hang out every day surfing, when they finally go, I feel like you really know that shit’s going down." It's the first taste of the apocalyptic: a vision of an abandoned beachfront, like something out of a disaster movie.

The next verse seems to take place back on the singer's home territory, in the realm of the personal and familiar:

Out in the park, we watch the sunset

Talkin' on a rusty swing set

After a while, you went quiet

And I got mean

I'm always pushin' you away from me

But you come back with gravity

And when I call, you come home

A bird in your teeth

'I Know the End' is a song of comings and goings. We see it here in the dynamic between the two characters, the pushing away and the return, that accords with the image of the "rusty swing set". There's no stasis; the arrival is only temporary and soon becomes another departure. The stability of the home is not to be found.

In the second chorus, it's the singer who has to get out of there:

So, I gotta go, I know, I know, I know

When the sirens sound, you'll hide under the floor

But I'm not gonna go down with my hometown in a tornado

I'm gonna chase it, I know, I know, I know

I gotta go now, I know, I know, I know

The tornado brings to mind the Wizard of Oz again, but 'I Know the End' inverts the structure of that story. Dorothy's tale is about departing from the familiar, going on an adventure and then returning once more. Bridgers' song begins and ends on the road, with home only a temporary stop.

It shares a feeling of transience with Dylan's 'A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall', from 1963. In that song, after coming home to report on his earlier travels, the singer, rather than remaining in shelter, heads back out into the dying world to bear witness to it, and to share what he sees with others: "I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it/And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it", he sings.

The singer in 'I Know the End' makes a similar choice. Rather than join her loved one in retreat "under the floor", she's "gonna chase it", and see what's going down in the altered, apocalyptic world. And, by singing the very song we're listening to, she's reflecting it to all souls: she's become a Revelator.

After the second and final chorus, the song shifts gears. Drums enter and the melody changes, as the singer hits the highway:

Drivin' out into the sun

Let the ultraviolet cover me up

Went looking for a creation myth

Ended up with a pair of cracked lips

Windows down, scream along

To some America First rap-country song

A slaughterhouse, an outlet mall

Slot machines, fear of God

Windows down, heater on

Big bolt of lightning hanging low

As she travels, the singer comes across the causes of her world's destruction, and indeed, many of the drivers of the climate, ecological and other catastrophes we face today. It's a very American nightmare. There's mainstream conservatism ("some America First rap-country song"), cruelty ("a slaughterhouse"), consumerism ("an outlet mall"), private interests taking advantage of human frailties ("slot machines"), religious fundamentalism ("fear of God") and wastefulness ("Windows down, heater on").

And then, there's an Unidentified Flying Object:

Over the coast, everyone's convinced

It's a government drone or an alien spaceship

Either way, we're not alone

In an interview with Stereogum, Bridgers said these lyrics were about a drive along the Californian coast:

I was driving up one time with my friends in high school, to go to Outside Lands I think, and there was a Space X launch — one of the first ones that I ever saw, that nobody knew about, and it looked like a weird fucking spaceship in the air floating. And everybody on the internet was like, “What the fuck is this?” There were at least 20 minutes where we were all like, “There’s aliens here.” I happened to be driving on the coast so I saw it over the beach, which was pretty surreal.

It's fitting that an apocalyptic song of the 21st century makes reference to one of Elon Musk's projects, in this case, space tourism venture Space X. Musk is sometimes portrayed as a climate saviour because of Tesla's advances in electric vehicles and battery storage, but it's more accurate to think of him as a false climate prophet. Journalist Emily Atkins convincingly makes the case that Musk's investment in space tourism and car infrastructure, as well as his conservative politics, mean he's had a negative cumulative climate impact. Beyond these specifics, the fact that anyone can possibly acquire as much wealth as Musk is part of the structural fucked-upness that has led to the environmental and social nightmares around us. A billionaire's private company bewildering the public by sending mysterious spaceships (and associated methane emissions) up into the air, all so other rich people can eventually go on planet-destroying holidays to outer space, certainly sounds dystopian to me.

I THINK WE JUST SAW A UFO IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA PLS EXPLAIN pic.twitter.com/TVsUJjmpR9

— hib (@hibabadook) December 23, 2017

Back on the road, the singer keeps driving, hanging out for somewhere to arrive at:

I'll find a new place to be from

A haunted house with a picket fence

To float around and ghost my friends

No, I'm not afraid to disappear

The billboard said "The End Is Near"

I turned around, there was nothing there

Yeah, I guess the end is here

There's nowhere to go. The haunted house is a phantom, and the singer's only destination ends up being apocalypse, now. At the end of the verse, there's only an absence, which is not so different to what there was at the start of the song. In the beginning, it was an internal sense of blankness. Now, the external world is also empty.

Why does the apocalypse fascinate us so?

I suspect a lot of artists (and readers and listeners) need it. Death and other kinds of endings are happening all around us, always, and imagining the end on a grand scale is one way artists and audiences can interrogate that reality.

Critic Norman Rosenthal, in the catalogue for an exhibition titled Apocalypse, makes the case that all visual art has apocalypse at its root:

Artists exist solely to make representations of the world using whatever means are available to them. They are there to draw attention to images and visual metaphors, to areas of the mind that we have not yet fully penetrated - not as scientists, not to tell us how things work, but rather to tell us what is actually at stake, to pull aspects of knowledge into a visual essence that can affect our perceptions. In this sense we can argue that all art is essentially apocalyptic: it challenges us, perhaps against our will, too look at the inevitable.

We might say all art is apocalyptic in so far as it unveils the truth. Often, that truth (like the fiery visions of Revelation) is frightening to comprehend.

As Rosenthal says, artists aren't scientists: we shouldn't look to apocalyptic art for accurate predictions or models of exactly how the future will unfold. Instead, apocalyptic art is useful for interrogating possible endings, what they might mean, how we might feel about them, and how we can respond to their prospect.

But let's take a few moments to consider the realm of scientists. It's worth asking, when it comes to the ecosphere and the damage wrought on people and planet by emissions-fuelled climate change, are we facing 'the end'?

It depends on what you're talking about. Is this the end of a relatively safe and stable climate? Yes, it's already gone. Will we see the end of certain low-lying island nations? It seems likely. Are we facing the end of freedoms afforded under democracy, as much as they exist? We very well could be, unless we fight to maintain and expand them. Will we see the end of globalised capitalism? Here's hoping, if we can manage it. How about an end to global human civilisation? It's certainly a risk, but it won't happen yet, and not necessarily. And the end of the human species? Scientists tell us there's no strong evidence to make us think it's imminent.

Climate journalist David Wallace-Wells argues that, while horrifying destruction is already here, a changing political context and the falling cost of renewable energy mean the direst predictions have become much less likely. "The window of possible climate futures is narrowing," he says, "and as a result, we are getting a clearer sense of what’s to come: a new world, full of disruption but also billions of people, well past climate normal and yet mercifully short of true climate apocalypse."

Wallace-Wells predicts warming will likely fall somewhere between 2 and 3 degrees before the end of the century. It's not exactly reassuring that we'll blow way past the 'safe' target of 1.5 degrees (although even that comes with disastrous impacts), and yet it seems we may be able to avoid warming of 4 or 5 degrees and the even more catastrophic impacts that would entail.

For some, particularly those in the global south, this mightn't be much comfort. I can imagine those who lived through the 2022 floods in Pakistan, which left thousands dead and millions displaced, feeling like they know the end. It's important we don't look away from this kind of climate suffering.

And yet, that doesn't mean nothing can be protected, that nothing can be done, or that we shouldn't try to minimise future impacts. Unlike for the souls facing judgement in the Book of Revelation, humanity's potential fate is not just to be either 'doomed' or 'saved'. There is a range of possible climate futures, not a binary.

As leading climate scientist Joelle Gergis writes:

The longer we delay, the more irreversible climate change we will lock in. Any young person can tell you that stabilising the Earth’s climate is literally a matter of life or death. It will impact the stability of their daily lives, their decision to start families, and their chance to witness the natural wonders of the world as their parents did. The ability of current and future generations to live on a stable planet rests on the decisions the world collectively makes right now.

By not hiding under the floorboards to look away from the apocalypse, we might be in a better place to make those decisions.

After the end, what comes next?

Like arrivals and departures in 'I Know the End', endings and beginnings follow each other naturally, and can sometimes be hard to distinguish.

In the Book of Revelation, the end of times is also a beginning: the Second Coming of Christ and the formation of "a new heaven and a new earth". For those lucky enough to escape the damnation of being "cast into the lake of fire", this is a wonderful thing, "For the Lamb which is in the midst of the throne shall feed them, and shall lead them unto living fountains of waters: and God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes."

After the end of a safe climate, and an extinction crisis causing the end of many species, what then?

Some talk about fresh beginnings and budding opportunities emerging from the climate crisis with a degree of optimism that makes me cautious. An extreme version of this unrelenting positivity is the belief that 'the planet will be fine in the long run; it's humans who will pay the price.' Sure, if you zoom out far enough you can see it like that, but there's an overwhelming amount of very real suffering left out of that picture.

And yet, there are openings presented by our current predicament. As our intensifying crises continue to show the shortcomings of capitalism, we need to be ready to cultivate and demonstrate alternatives, to 'build the new world in the shell of the old'. As established institutions increasingly fail and lose legitimacy, we need to be ready to step in with alternatives, grown out of the grassroots. There can be new arrivals and new beginnings, even amidst the suffering, of which there is much to come.

In Phoebe Bridgers' song, maybe there's a glimpse of something that comes after the end. There is, at the least, something that comes after the singer turns around and finds nothing there.

After a song (and an album) filled with loneliness, suddenly, in the final minutes of 'I Know the End', we have something unexpected: a spirited group vocal. "The end is here", repeats Bridgers along with a chorus that includes famous friends like Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, Christian Lee Hudson and Conor Oberst. Now, the end is faced communally. Perhaps what is offered is not so much a prediction for what comes after the end but a prescription for how we can confront it: alongside others with whom we find affinity, even as we may struggle with our own loneliness and despondency. There's power in finding others who feel as we do, and in expressing those feelings to them and with them.

At the end of the song, there's a scream, a long one at the climax that extends into the dying moments and beyond, once the instrumental backing is gone. It's not a Little Richard rock n' roll scream, but an existential heavy metal scream. Here is a catharsis that comes from confronting existential questions, taking a hard look at the crumbling world, and expressing what is witnessed.

As I was putting the final touches on this essay, I caught the last bit of a song on the radio. My attention was captured by the repeated refrain which reminded me of 'I Know the End': "Is this the end, is this the end of our people?" I looked it up; the song was 'Listen to the News', from the 1990 musical Bran Nue Dae by Bardi and Nyul Nyul playwright Jimmy Chi, a coming-of-age story about an Aboriginal boy who escapes a mission school and returns to his homelands.

The song was a reminder that colonised people have long been experiencing loss on a massive scale. "Listen to the news, talking 'bout the blues of our people", the chorus goes. In so-called Australia, some First Nations cultures have been decimated by colonisation, and all have suffered massive disruption. “Colonisation was our apocalypse, and we are already living in a dystopian future, so we are ahead of the game,” Gunai, Gunditjmara, Wiradjuri and Yorta Yorta writer Nayuka Gorrie has said.

And yet, Bran Nue Dae and 'Listen to the News' themselves are also examples of cultural resilience and renewal.

The evening before I heard the song, I'd read an article by Anthony Ham in The Monthly about Warlpiri elders passing down tracking skills to younger generations. Here was another example of resilience in the face of destruction. The article describes the cultural transmission project as taking place against a "backdrop of loss and renewal", with some ecological and cultural knowledge irrevocably gone, but some of it able to be held onto and passed on. By taking part in the project, the Warlpiri people also gained learnings about their country as part of "two-way science", in exchange with non-Indigenous knowledge systems. Even in times of great hardship, some thread continues.

Watching a video of the original Bran Nue Dae cast performing 'Listen to the News' at the Stompen Ground festival in Broome in 1992 reminded me of something else: the joy possible in adversity.

In that Genius interview, Phoebe Bridgers says 'I Know the End' is about:

Just kind of being at peace with the end the world. And I don't mean in an apathetic way. I just mean, instead of waking up every day during the apocalypse like right now, and being heartbroken, you're just kind of like, 'Okay, what can I do today?' Taking it kind of a day at a time instead of giving up.

Bridgers says the apocalypse, the ending of the world, is happening right now. I'd say the world is always ending, just like it's always beginning. Looking at the world now, you could say, as William Butler Yeats did of his world of 1919, that it seems as if "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold". Who knows what kind of beginning will follow our end and what will end up being born?

Okay, what can I do today?

For me, I try (not always successfully) to direct my energies towards some combination of activism, creativity, service and practice. I aim to throw a little wonder and awe in there as well.

And I make time to listen to good songs. Just for the pleasure of it, and also because they lead me to ask myself the right questions.